Note: I think it’s fun to publish personal essays every now and then on this blog, so skip this if you mainly follow me for biology content.

Between July 2023 and January 2024, I read between twenty and thirty novels, a sizable number in its own right, but especially meaningful in light of it being the first time since childhood that reading felt urgent. Something of the utmost priority. None related in any meaningful way to what I write about on this blog. They were fiction, unrelated to biology, and I imagine the primary reason their authors wrote them was to impart one singular emotion to the reader.

Pain.

Prior to my season of reading, I had felt off. One might call it melancholy or disquiet or malaise, but those terms feel too definite, too grand. It was something more subtle, fleeting, difficult to fit into language. It was a background emotional sensitivity, the kind that leaves one inexplicably tearful during something as normal as a movie trailer. Does that make sense? A type of ambient eeriness you expect to carry during your teenage years, something you naturally assume you'll outgrow as your brain matures. But one painful realization of growing older is that while your expectations for personal dignity evolve, the emotions threatening that dignity often stubbornly remain the same.

In time, these feelings demanded emotional texture. Something wiry to grip onto, contours, edges. I visited a bookstore with the firm intention of satisfying this desire, and left with a copy of My Year of Rest and Relaxation, by Ottessa Moshfegh. I had wanted to read this book since it came out in 2018, but it never felt like the right time. I think some works shouldn’t be consumed if you don’t feel like you’re ready to grasp what the creator of it meant for you to feel. This is not out of respect to the writer or director or artist, this consideration is for you and really you alone. There are only so many good things in the world, and only so many chances to be cracked open by them. Being cracked is a wonderful feeling, so you should wait for the right moment to achieve it.

My Year of Rest and Relaxation is about a woman who feels so exhausted with life that she desires to sleep for a year straight via chemical means. Through a cadre of seedy psychiatrists and drug dealers, she assembles together a cocktail of sedatives and opiates and tranquilizers to achieve this, waking only for an hour each day to have a small meal, some water, and an exercise routine to prevent muscle wasting. But this is the ‘climax’ of the book. Much of the narrative is first spent circling that comatose desire, spiraling through the protagonist’s apathy, passive aggression, and hatred for the life she has curated for herself.

Sleep, she believes, will purify her. If she can just stay unconscious long enough, the parts of her life that feel intolerable might slough off on their own. Her body, infinitely kind and patient, simply needs the uninterrupted time to do that. The protagonist is never given a name, because she really isn’t the point of the book.

I’ve come to suspect that this type of untethered misery, the kind without a cause, has more to do with narcissism than anything else. I’m not the first one to make this connection. The Last Psychiatrist probably did it first:

Narcissism says: my situation is different. I am not like other people, who are merely automatons, shuffling towards oblivion.

But of course, nobody wants to be narcissistic. Most are simply unaware of it, how much we desire to be the main character, the one whose pain is deepest, most complex, most worthy of attention. We don’t necessarily want sympathy; we want significance. We want our sadness to mean something.

But the hedonic treadmill awaits. To those who are in genuine pain, who are performing experiments upon themselves to relieve the agony, do they seem happy? Do they feel significant? Do they? Do they? Well, maybe at the start. Maybe in the brief, narcotic haze of a new theory, a new identity, a new chemical. But misery rarely sustains meaning. It dulls. It becomes bureaucratic.

When I read Ottessa’s novel, the sadness felt by the main character of the novel felt like it belonged to me. All of her numbness, her passive disdain, her impulse to vanish beneath a weighted blanket of pharmaceuticals. My brain gorged on the grotesque theatricality of it all, her fictional suffering mine to borrow, to imbibe momentarily. I hated the beautiful things she hated, I loved the awful things she loved. But the more I read, the more her sadness began to feel stylized. Of course, it was stylized from the start, but it takes pages upon pages to realize it! Her pain had clarity, direction, aesthetic coherence. Too much of it! It was a supernormal stimulus, so overt in its legible bleakness that it became almost garish. A spectacle.

As a result, I began to find my own malaise embarrassing, just as I found her malaise embarrassing. Not because either was false, but because both had started to feel indulgent, mine in its shapelessness, hers in its choreography. In this sense, painful books serve as a reflection, a moment to reconsider is this what I’ve been doing? Is this what I’ve been feeling?. Sometimes the answer is an enthusiastic yes and ‘thats okay’, things have been quite awful after all. But sometimes it’s a quieter yes and ‘perhaps it’s time to stop’, an admittance that the emotions you've been nursing are based in a previously unconscious grandiosity.

But not all painful books are meant for reflection. Sometimes they are meant as a warning.

When I was 15 and in a similar mood, I read Stoner, by John Edward Williams. The book is a fictional biography of a man named ‘William Stoner’, walking through his early childhood, adult life, and senior years. William Stoner’s life is quiet, uneventful, and profoundly depressing. Not in a stylized way, but in the way a table rots, or wallpaper yellows, or a man forgets why he married his wife. Nothing explodes. No revelations arrive. He simply endures. It’s not a tragic story in the conventional sense, there’s only time, pressing down.

Stoner was published in 1965, which came to some surprise to me after finishing it, because the tinge of desperation in the main character has a very modern feeling to it. Unlike Ottessa’s protagonist, Stoner doesn't hate the world theatrically. He barely reacts at all to the slow erosion of his hopes, his work, his relationships. In many ways, the novel is an allegory of stoicism, but a brand of which that I found nauseating. Stoner doesn’t transcend his pain, not really, he simply absorbs it until it becomes indistinguishable from his character.

At fifteen, this was horrifying to me. I had no vocabulary for that kind of resignation! I thought life was supposed to be dramatic, shaped by decisive moments and meaningful choices. It jolted me out of complacency because, unlike him, I could still choose differently.

I think I have. Or, at least, I have tried in decade-plus since.

Either way, I felt fixed. Over six months, Ottessa-esque books had helped me realize how self-indulgent my emotions were, whereas Stoner-esque books had reminded me how passive awareness of negativity is not the same thing as resistance to it. Recognizing despair is easy; doing something with it is harder. And simply naming your unhappiness, no matter how eloquently, doesn’t absolve you from the responsibility of moving through it.

With my new-found happiness, I settled on more sustainable forms of self-care, like eating a few eggs every day and going on long, undirected walks.

So I largely stopped reading.

But if painful books are so useful, why stop at all? Why not endlessly pursue perspective through emotional discomfort? There is an archetype of individual who does exactly this, constantly simmering themselves in the newest and greatest in media-based torture. They read only the bleakest literature, watch only the most devastating films, and write long-winded essays—like this one!—about the moral and psychological rewards of feeling very, very bad. They believe that pain is not only clarifying but ennobling, that suffering polishes the soul like sandpaper against raw wood.

But, eventually, external emotional pain ceases to offer meaningful perspective and instead settles into your psyche, becoming indistinguishable from emotion that uniquely arose from within you. You begin to inhabit borrowed sorrows rather than confront personal reality, effectively replacing authentic self-awareness with a carefully curated imitation of suffering. Given enough time, melancholy goes from an unfortunate outgrowth of narcissism to outright comfortable. No longer a catalyst for change, instead morphing into a habitual form of indulgence disguised as introspection or emotional depth.

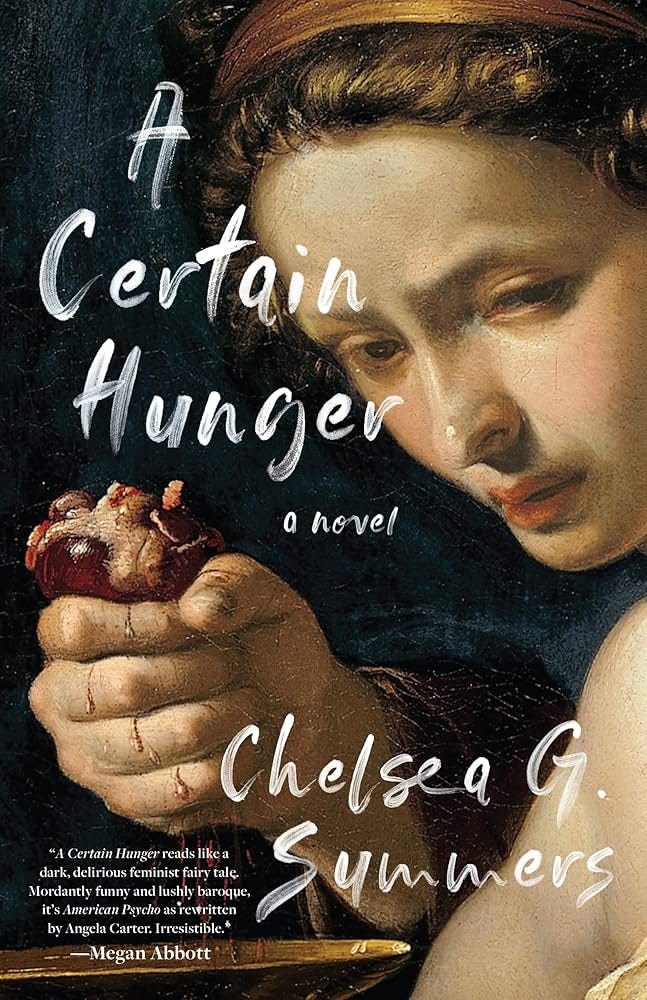

Of course, despite being aware of this, I still felt an urge to continue. While the last painful book I read was Life Ceremony by Sayaka Murata, it wasn’t the last one I bought. That honor belongs to A Certain Hunger, by Chelsea G. Summers. It had a beautiful cover, though the reviews aren’t fantastic.

But I never started it. I immediately felt regret after having bought it, loaned it to a friend, and never asked for it back.

Usually I wouldn't recommend *House of Leaves*. That book is deeply unnerving. But if you're seeking out painful experiences, it might be interesting for you.